Gold, Guns and God: Vol. 10—The Final Pastimes

Foreword

A Biography of Swami Bhaktipada and a History of the West Virginia New Vrindaban Hare Krishna Community in Ten Volumes by Henry Doktorski

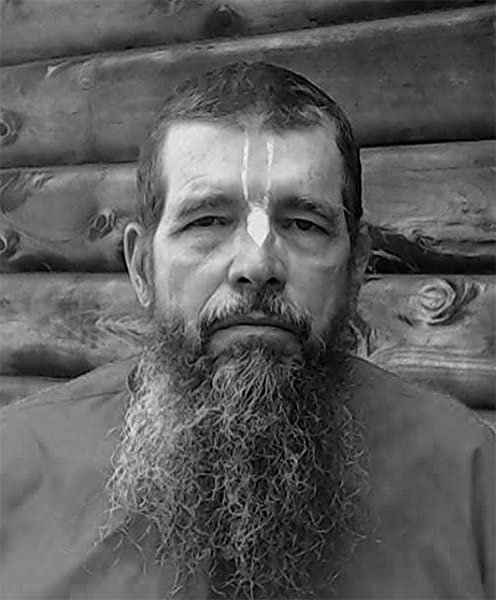

Kailasa Candra dasa was initiated in September 1972 at New Vrindaban

by Kailasa Candra dasa

Nestled in the wooded ridges and hollows of the Allegheny Plateau in the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia, there had emerged, in the late Sixties and early Seventies, a rural forest compound which became the image of its founder. That enigmatic and charismatic man was one Kirtanananda Swami, who led a life of contradiction and irony.

That place came to be known throughout the Hare Krishna movement as “New Vrindaban,” a moniker only partially deserved, at best . . . but, admittedly, it was something new.

Kirtanananda was, from his entering the Krishna movement, a developing cult controller with an acute ability to press the right psychological buttons inside of any person who entered his wheelhouse. This was particularly the case for those who were fascinated with him and enchanted by him.

He always considered himself to be number one in comparison to his godbrothers: He was amongst the first initiated disciples, the first devotee to become a master cook, the first to accompany his spiritual master to India, and the first to receive the sannyasa order. He was also the first to defy his guru.

Previous to his coming to the movement, he was part of the Mott Street Gang, all of whom became members of ISKCON.[1] One of those members insisted that they all considered each other as equals; in all likelihood, however, Kirtanananda considered himself the best of those equals. As his previous devoted follower (but eventual chief antagonist), Sulochan dasa once asked the following question: “Who has ever seen Kirtanananda offer his obeisances to any of his godbrothers?”

Kirtanananda was a short fellow with bad teeth. He had an unmanly, high-pitched voice. He aged quickly. He was sickly as a teenager, if not as a child. Due to polio, the muscles in his abdomen were damaged and consequently he had a pot belly and problems with hernias. His belly shook like a bowl of jelly and swayed from side to side when he walked. He was raised as a Protestant, and, from one perspective, he remained a kind of protestant throughout his life. He was not a good looking man by any objective measure, and he was a homosexual. To one of his early godbrothers, he once confided, “I’ve been sucking cocks since I was five.” He claimed to be impotent; he couldn’t get an erection, at least from the age of fifty or so and probably earlier.[2]

Despite these demerits, Kirtanananda was a driven personality with a quick wit, philosophical acuity, and a demeanor which he parlayed into something big for himself. He did not hold any face cards, but he drew into an inside straight flush and made the most of it. His astral tendency was compulsive, but he had the intelligence to control it. Indeed, he soon learned how to dovetail that in controlling the chelas of his personality cult.[3]

He had bold ideas, and he formulated them in such a way as to make them successfully mold into form. He envisaged the plot as much as he constructed it. He also knew that the overwhelming majority of people—including Krishna devotees—were far more prone to imagination, wonder, and fascination than they were to intelligence and logic. Those who were exceptions to this rule did not stay in “New Vrindaban” and rarely even visited.

He was a user. His Moundsville compound was the movie he was making, and he was both its script writer and director. He was also its producer, although he used others to come up with all of the money needed to keep financing it.

He was an adept at emulating a sense of the uncanny. It was expressed in his particular art form there, and it was expressed even in his life. He was not obliged to explain himself to anyone, and there is no record of him ever having done so. He could churn the ocean of anxiety and fear, combining it with that all-pervading sense of the uncanny; his rural wonderland thrived in just the way that he wanted it to develop.

He experienced great satisfaction in this, as he not only enjoyed the best of both worlds, but he exploited the best of all worlds. He despised Kierkegaard, because it was never a question of either/or for Kirtanananda; he wanted it all! He fooled almost everybody. He implemented the black art of making no one feel that they had been fooled or swindled, making him the greatest bogus guru; again, number one.

There was always an element of anticipation amongst “the inmates” at his quasi-Disneyland. He initially cashed in with beautiful Deities in order to supplement and complement those designs and that ambiance; by this, he gained significant credibility, along with the pretense of authority.

He knew how to project a combination of mystery and authority in order to make sure that he was the cynosure of attention with exclusive access to all of the toggle switches. Although almost everything about him was incredulous, he was able to keep that at bay through honed psychological manipulation, which would have made Machiavelli look like a piker.

Which should bring us to his character, deeper than the many iterations of his personality. First however, let us consider some of those personality vicissitudes. Let us begin with his transition to early hippie after a brief dip into the truncated beat years. He was said to having become a Sixties LSD guru while leading the aforementioned Mott Street Gang, one of which was his homosexual lover from previous college days. Others dispute his LSD guru hood, but the germ was planted at that time.

Still in New York City, he segued to become a pukka brahmachari, apparently surrendered to his Vaishnava spiritual master from West Bengal. He was the oldest devotee to join the movement, making him number one in that category, as well. After that, he segued to being the personal servant in intimate contact of said guru, accompanying him to India in the second-half of the Sixties.

From there, he became the first sannyasi in the Hare Krishna movement. Then, showing his real face by disobeying the orders he had received for preaching in Britain, he instead joined back up with his homosexual buddy in The City. During that brief stay, he tried to radicalize and change his spiritual master’s preaching strategy at a fundamental level.

Fully rejected by his godbrothers, he donned a black robe, black apparel, and a black, imitation danda, roaming the streets. After that craziness ran its course, he joined his aforementioned lover, Hayagriva, an accomplished professor, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. It is rumored that he took sexual advantage of some of the community college students there.

This location was close to what would eventually be his Shangri-La garden of good and evil in West Virginia. He freely lived on that land for a while. Then Hayagriva negotiated, with a thirty-seven percent down payment, a four thousand dollar purchase of a ninety-nine year lease on the property. To sum up these months, Kirtanananda lived off of Hayagriva’s money.

He then became a humbled repentant with tears in his eyes, begging forgiveness from his guru (who he had lost the link with), in the process of such disconnection having been derogatorily labeled by his former guru as “a crazy man.”

Defying warnings from his guru that the “New Vrindaban” idea would probably wind up unsuccessful within that “Deliverance” paradigm of low-class, suspicious men in the Moundsville area, he went through with his plan anyway.

Somewhat surprisingly, he was able to make a go of it. His personality then appeared empowered, as he was finally able to accomplish something tangible. His ontology included all of these various and contradictory personalities.

They were later augmented substantially when he became the initiating spiritual master of his own personality cult. He also then became a kind of mafia don, ordering hits on his enemy godbrothers, after first transitioning to the identity of a pretender maha-bhagavat via the moniker “Bhaktipada.”

His operation at the Moundsville compound was shot through with criminal activity. Most of it was known and sanctioned by the man. In due course, he became a convicted felon serving significant time in penitentiaries.

That was the man of many faces on the astral and physical plane, but what was his actual character? It was one. Judge by the results. If you actually do so, you will have to admit that his character never wavered or changed. At root, he was a warlock developing power in the guise of a spiritual leader.

Absorbed in self-apotheosis for years, in the last week of December, 1977, Kirtanananda made the wrong move at the right time: He began initiating his own disciples according to his own prerogative. It was another first and a huge gambit. He decided, without any consultation, to also take maha-bhagavat worship from not only newcomers to his magical mystery camp, but to be adored in that way even by all of his godbrothers and godsisters living there under his ultimate control.

Stretching the rubber band to the max, he was able to pull it off during quite a run of tremendous good luck, although it would have to end badly. His wrong move of 1977, less than a month and a half after Prabhupada had left the scene in India under nefarious circumstances, is more accurately understood as not merely wrong, but utterly deviant. With accomplices, it led to Kirtanananda Swami destroying the whole movement.

He beckoned newcomers to believe that what he offered them was a spiritual experience. There was a lot of covert stuff that went down behind the scenes in his personality cult. Its plot threads were mostly in-house, and whatever lurked behind the curtain there raised its ugly head in due course of time.

Why did so many of his followers fall for his personality and his pretense? The answer to that is as simple in principle as it is complicated in detail: They all wanted to be cheated, and they wanted to be cheated by a man just like him. They were all spiritually dull-witted. As His Divine Grace Prabhupada said during a Q & A from his Vyasasana in Honolulu in the Spring of 1974: “Dull-witted must be cheated. I am pleased. Krishna is pleased. Why are you displeased?”

That cult backdrop of New Vrindaban was both eerie and surreal, and it had a very dark side—an underbelly—permeating all of the distortions reflected by its fun house mirrors, along with a combination with colorful rituals, festivals, and even a Palace. The community which subsidized it approved of its witch’s brew of mystique and alleged spiritual authority. It appeared to be a juggernaut, and for a while it was.

“New Vrindaban,” however, was inherently unstable; it could crumble at any time. In due course, it did just that. The opulent Palace became a doppelganger and dollar drain in a state of ever-increasing disrepair. His Moundsville compound cratered fast, and he went down with it. It was built upon a foundation of sand, and that beach was made up of Kirtanananda’s compromises and defiance of Prabhupada’s orders.

New Vrindaban soon became the anachronism of the Hare Krishna movement. It became an odd place with a great deal of imagination in it, most of that being connected to the so-called divinity of Kirtanananda. There was also a kind of ghostly haunt pervading it, suffused with a whiff of the uncanny.

The legacy of “New Vrindaban” is one of meta-deception, and it still is. It was not what it seemed, because that man ruling it was not what he seemed. Kirtanananda’s personality, character, and life were loaded with contradictions; the end of his life was, in three distinct ways, also loaded with irony.

Contradictions. He was a sannyasi, and renunciates have nothing to do with monarchy. Although he was a despot for those inmates serving under him, he was a despotic sannyasi, and, in many ways (but not all), a strict one. Yet, after assuming his “Bhaktipada” moniker, he placed an opulent crown on his head and carried a royal mace while sitting on his dais.

There is a photo of this, and he is clearly enjoying himself in it. Although it might have been a one-off, this monarchical demonstration was a blatant contradiction and forbidden for anyone in the order of renunciation, despite his chelas loving him even more for the pretense.

It didn’t stop there. Inside the Palace, he ordered a similar crown to be placed on the head of the murti of Prabhupada, although there is no record of His Divine Grace ever training as a monarch, or speaking or acting as a king.

Sure, Kirtanananda was strict in his daily routine. He rose early and invariably took a cold shower. He ate light and sometimes sparingly. Yet, at the same time, in private, he was an active homosexual. This contradiction was hidden from most of his disciples, but it burst out into the open in 1993, a scandal known as the Winnebago Incident. The man stretched the rubber band for many years, and it finally snapped.

Although most would consider that contradiction to be the fatal blow, such was not the case. The contradiction that actually did him in was previous to the Winnebago Incident, and it was related to the Governing Body Commission.

As is well-known now, he began initiating and taking opulent maha-bhagavat worship without consulting the Board or any of its members; he did so well before the scheduled GBC meeting in the Spring of 1978. By that action, he let it be known to the movement that his level of realization and spiritual power was such that he could call his own shots in any way that he chose. By his bold action, he self-declared the independence of a raga-bhakta or a God-realized soul.

Surprisingly, he then compromised in the Spring of 1978. He did so by accepting an initiation zone from the GBC. This solidified his hold to a practically negligible extent in New Vrindaban and its satellite centers, where he already had full control previously. Accepting that zone strengthened him little, but it did limit him, as it was a concession to GBC authority, which he had defied just after Prabhupada left the scene.

He had enough intelligence to know that it would have to come to a confrontation with the GBC in due course of time. It would have been to his advantage to have that showdown while he was at the height of unfettered power. His bold move had already laid down the gauntlet, but it was compromised by this glaring weakness, which was a stunning contradiction.

Irony. At the height of his power, he was the despot of all devotional despots. No one dared defy him. All authority was delegated by him, and it could not be maintained unless he sanctioned it to continue.

Yet, most ironically, he wound up a broken man, driven out from his Moundsville playground by a committee of his former fervent disciples and godbrothers. Their fanaticism cultivated by him turned against him, and he had to take shelter of other disciples and followers in New York City. As fate would have it, those disciples and followers also drove him out of a small apartment that had been given to him. This forced him out of America entirely and to the subcontinent, the same India that he had expressly detested in the Sixties for its dirtiness.

His track record was anything but cooperative with the GBC. He railed against how it operated, how it ran the movement, and what it stood for; his protests against it were legion. In that sense, he was and remained the premier protestant within ISKCON, and he was quite the Protestant also before his transition to college led him to assimilate a Bohemian lifestyle. Yet, quite ironically, he died of kidney failure in a predominantly Catholic enclave just outside of Bombay.

The final irony was after his death. Instead of burning his body at a pilgrimage site in the extended region of Bombay, his dedicated and foolish devotees decided that he had to be taken to Vrindaban in Uttar Pradesh. Their idea was that he was so special that he had to be interred in salt there and not cremated, although he deserved no such honor.

These idiots tried to preserve a rotting body with ice on that long train trek across the western half of India, and it proved to be a disaster. The ice melted quickly, and his body began decomposing in the Indian heat inside of a hot train car.

Added to that horror, there was a delay in securing a site for his burial in Raman Reti. When his disciples and godbrothers came to pay their last respects to his corpse, it was bloated, discolored, and completely beyond recognition. Photos were taken of this. The final irony was that his devoted followers, in their fervor to honor him, did just the opposite, creating a macabre scene which is now still framed into posterity.

A Foreword, by definition and substance, cannot and does not delve into comprehensive and granular details. Those now eagerly await you in the form of Volume Ten, the final volume of this Gold, Guns and God series by Henry Doktorski. His super-excellent research is capped off with a great chapter explaining the saga of Kirtanananda in meticulous and stunning detail.

Like all of his previous ones, this volume is a page-turner. The meta-deception of what was (and now still is) the New Vrindaban escapade—and its founder and previous despotic leader—is further explained threadbare. This Tenth Volume comes highly recommended. It will help you to better understand the saga of one Kirtanananda Swami, the man who would be king.

Kailasa Candra dasa, ACBSP (Mark Goodwin)[4] Gaudiya-Vaishnava teacher, author, sidereal astrologer and co-founder of the Vaishnava Foundation Boston Mountains, Ozarks, Arkansas April, 2022

Photo of Kailasa Candra dasa taken in 2014 on the back deck of his cabin.

Endnotes:

1. Keith Ham, Howard Wheeler and Wallace Sheffey (Kirtanananda, Hayagriva and Umapati) lived in apartment 3-A at 274 Mott Street in the Lower East Side from July 1962 through the summer of 1966.

2. As noted in Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 9.

3. A chela is a dedicated disciple, especially one who has a close and loving relationship with the master.

4. For more about Kailasa Candra dasa, visit his Wikipedia page.

| Back to: Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 10 |