Gold, Guns and God: Vol. 8—The City of God

A Biography of Swami Bhaktipada and a History of the West Virginia New Vrindaban Hare Krishna Community in Ten Volumes by Henry Doktorski

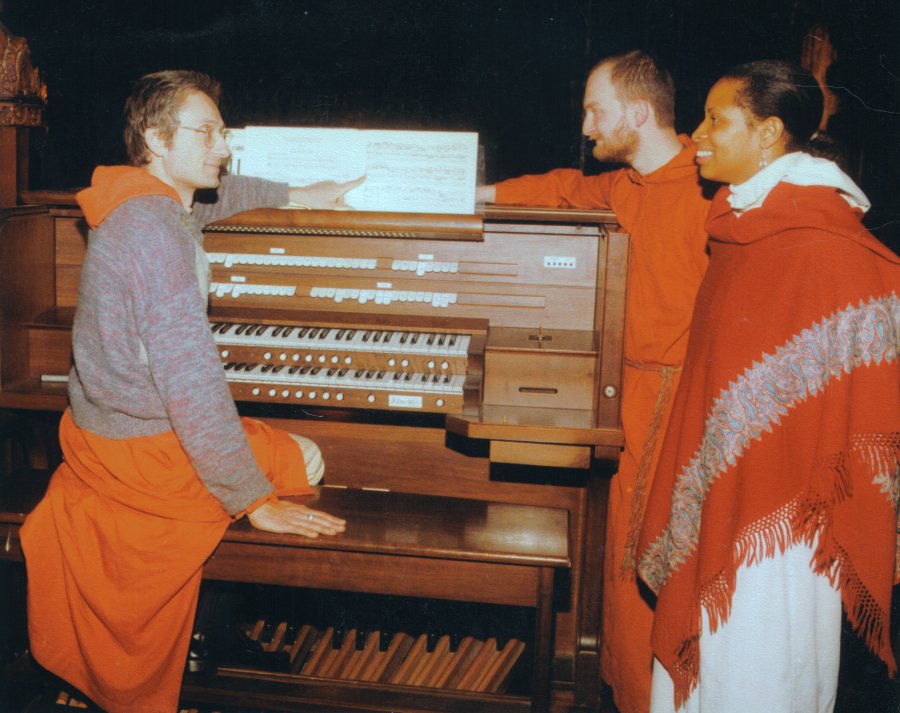

Hrishikesh with cantor and harpist Bhavisya, and accordionist and timpanist Dutiful Rama at the console of the Allen electronic organ. Photo from New Vrindaban World, Vol. 1, No. 1 (February 1990).

by Henry Doktorski

I FOUND THIS VOLUME OF GOLD, GUNS AND GOD extremely enjoyable to research and write, because a good portion of this book deals with the music I composed, directed and performed under the order of my spiritual master, whom I affectionately addressed at the time as Bhaktipada. It was in 1986 when Bhaktipada began in earnest his “Great Experiment,” his Krishna-conscious “Reformation”: the de-Indianization of Krishna consciousness, although he had introduced a few elements from Christianity into New Vrindaban a few years earlier.

During the spring and summer of 1986, I was out on the pick with my brahmachari buddies collecting money for New Vrindaban. Once a month however, for three days, we got to visit “The Farm,” as we called New Vrindaban at the time. Instead of sleeping on the third floor of the RVC temple with the other single men, most of us pickers slept in Bhaktipada’s basement to be closer to our spiritual master and relish his association. Bhaktipada was always affectionate to us, as I recall.

At Bhaktipada’s house I enjoyed the close proximity with my spiritual master, and every night after the evening service in his temple room my brahmachari buddies and I tiptoed into Bhaktipada’s bedroom, sat on the floor, and hung out and chatted with our gurudeva for fifteen or thirty minutes.

Around that time, Bhaktipada began acquiring a large compact disc collection of recordings of organ and choral masterpieces by great European Renaissance, Baroque and Classical composers. He especially had a fondness for the music of the great German Baroque organist and composer Johann Sebastian Bach, who also happened to be one of my favorite composers. Sitting on the floor in his bedroom, we listened to inspiring music emanating from his home stereo speakers. Bhaktipada often remarked, “How can anyone NOT think of God while listening to this music?” The music was grand and uplifting and often elicited profound thoughts and emotions in our minds and hearts.

Soon after, in October 1986, Bhaktipada ordered me to stop my fulltime service as a picker, move to the Farm, and start a choir to sing great Western masterpieces in which the lyrics had been Krishna-ized to express the sentiments and philosophy of the Gaudiya Vaishnavas. Eventually he also commissioned me to compose music for the three daily temple services—morning, noon and evening—and recruit and direct an orchestra of devotee musicians (a substantial ensemble which included strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion, and the all-important pipe organ) to support our congregational singing.

Bhaktipada’s Great Experiment lasted about eight years, and I thoroughly enjoyed my service as New Vrindaban’s first (and to date only) Minister of Music. I used to play three services per day; twenty-one services per week. I played the organ twice daily: 5 a.m. at the morning service, and 12:00 p.m. at the noon service, and I played the accordion at the 7 p.m. evening service. I think most professional organists today would faint if they had that work load.

The music I composed was literally performed thousands of times, beginning in the summer of 1988 when we established the English Western classical music services, until the English services were terminated in the summer of 1994. During those six years New Vrindaban hosted more than six thousand temple services featuring my music.

Bhaktipada’s “Palace”

During our bedroom darshans with our gurudeva, my godbrothers and I sometimes asked Bhaktipada, “You built a palace for your spiritual master. In the future, can we build a palace for you?” Bhaktipada usually answered, “Only if I give you permission.” We knew that he would never give us permission, as we would never have the time nor money to build a palace for our spiritual master. We were already engaged seven days a week in helping him build New Vrindaban and the great Radha-Vrindaban Chandra Temple of Understanding and Land of Krishna.

However, when I became Minister of Music, I realized I could finally build a palace for Bhaktipada: a palace made not from concrete, marble and gold, but a palace made from sound vibrations: four-part counterpoint sung by soprano, alto, tenor and bass voices, and accompanied by pipe organ and other instruments. Part of my service at New Vrindaban consisted of composing and arranging music for our choir and musicians, and in 1986-1987 I composed a ten-minute-long three-part four-voice contrapuntal setting of the Bhaktipadastakam Prayers which our choir premiered (in part) at our January 1987 concert in the temple and recorded (in full) on our 1988 “Jagad Guru” cassette tape.

The piece ends with a grand finale; a four-voice fugue based on the Hare Krishna maha-mantra tune which Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada first presented to his disciples at 26 Second Avenue some twenty years earlier. This musical offering was the “palace” I built for my spiritual master. Bhaktipada was extremely pleased and proud of our Western music program (and expressed this in conversations and letters), and many, many residents and visitors appreciated the morning, noon and evening services (and concerts and musicals) which they found beautiful and inspiring.

Of course, not everyone liked our Great Experiment. Some New Vrindaban devotees preferred the traditional ISKCON Bengali-style kirtans and bhajans. I remember performing at the organ console during the noon service, probably in 1989, when Murti dasa (Michael Dilly), who worked at the barn and later in heavy equipment, entered the temple room and walked past the organ console. He gave me a sour face and a “thumbs down” signal with his hand. I had to agree with him; some of our musical and liturgical “experiments” were less than successful. I did not like that particular hymn myself, and I dropped it from our repertoire.

And yet on another note, I didn’t care if some people didn’t like our music, as I was basically only concerned with pleasing my spiritual master. I knew the Western music program was controversial, but it was dear to Bhaktipada. I wanted to be dear to my spiritual master by adopting his mood and serving him. Actually, I didn’t have to adopt his mood; we truly were kindred spirits, as far as music was concerned. During the six years of our Western music experiment, we never disagreed on anything, as far as I recall. Our minds were one.

However, “All things must pass“—as George Harrison sang in his 1970 triple album of the same title—and eventually a grass-roots reaction formed at New Vrindaban to return the temple music to the ISKCON style. It gathered momentum (especially after the September 1993 Winnebago Incident) and succeeded in terminating Bhaktipada’s Great Experiment in July 1994. The reasons why Bhaktipada’s Reformation dissolved will be thoroughly explained in Vol. 9.

Despite the conclusion of many, including myself eventually, that the Western classical music program was not appropriate for a holy place of pilgrimage such as New Vrindaban—a community which had been established under the direction and guidance of the Founder/Acharya of ISKCON, His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who gave explicit and detailed instructions for the atmosphere he wanted to create there—the music we produced, in my opinion, had merit nonetheless, and would most certainly be perfectly appropriate perhaps at another place and time.

After the morning, noon and evening service music at New Vrindaban had been established, I think late in 1988, Bhaktipada told me, “Your music will one day be played throughout the world.” At the time, I thought if his prophecy was to become fact, it would be because of the success of the New Vrindaban City of God, and the other eleven proposed Cities of God throughout the world.

In the early- to mid-1990s, my music was performed at more than a half dozen New Vrindaban satellite centers: the New York City Interfaith Sanctuary, the Columbus and Cincinnati, Ohio preaching centers; the East Bridgewater, Massachusetts preaching center; and centers in Toronto, Ontario; Montreal, Quebec; and even overseas in the Netherlands and Malaysia.

However, when Bhaktipada was rejected as acharya of New Vrindaban and the English temple services were terminated in July 1994, I thought perhaps Bhaktipada had erred in his prophecy. That was (and is) fine with me, as I was (and am) not attached to the results of my service, to a great extent, at least. Yes, I served Bhaktipada faithfully for fifteen plus years, but after I rejected him as my spiritual master, my life took on a new direction. A few months later, I left New Vrindaban and shook the dust of the Holy Dhama off my feet, although during the twenty-two years when I lived in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, I often visited, especially during festivals.

I personally thought the music I helped create, under Bhaktipada’s direction, was beautiful and inspiring. But if others appreciated my music, or disliked my music, I was unattached. I understood in my heart that the nonpermanent appearance of happiness and distress, honor and dishonor, fame and infamy, and their disappearance in due course, are like the appearance and disappearance of winter and summer seasons. They arise from sense perception, and one must learn to tolerate them without being disturbed.

I feel the same way about my books, Killing for Krishna, Eleven Naked Emperors, and the Gold, Guns and God decalogy. If people appreciate these books, fine. If they don’t, that is also fine. I learned a lot about life from my time with the Hare Krishnas, and after I left New Vrindaban in 1994, I have benefited greatly in many ways from my studies and practice of bhakti-yoga during my earlier years: when I was a young man in my twenties and thirties. Now I’m 66 and approaching old age. Detachment from the results of one’s actions is a great gift and source of happiness to me, and I am grateful for the important life lessons which I learned at New Vrindaban while studying and practicing bhakti yoga under Bhaktipada’s direction. Despite Bhaktipada’s faults (and he had plenty), I learned a lot from him, and my life, at least, is better for having known him.

In fact, you may discover an entirely new facet of Bhaktipada’s persona in this volume. One of my friends, a student of bhakti yoga, wrote to me after proofreading Volume 8:

Dear Henry,

After reading your proof copy of Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 8, all I can say is, that’s a lot of music! I’m fascinated by the musical ambitions and the installation of the pipe organs. It’s insane to read all this went on Henry. Actually, baffling.

What I mean is: I had no idea how elaborate the music program became in New Vrindaban during your tenure there, and especially after New Vrindaban was expelled from ISKCON in 1987-1988. Between getting those pipe organs, the chorale, the orchestra, the music theater, and how much you were performing, I’m amazed.

Honestly, this volume is the first time that Keith Ham is becoming human again, from my perspective. I’ve been too quick to take the easy road and just call him a sick man, a child molester or a master manipulator; this in spite of the fact he was proven to be all the aforementioned. However, these musical endeavors, his attempt to blend religious traditions, and his work in creating an interfaith City of God suddenly makes sense. His intentions were clearly more noble than I originally thought.

It feels like you’ve opened my mind. Keith, from the beginning, was a proven deviant who disobeyed Srila Prabhupada, so I have always dismissed him as such. His ideas about Christian-izing Krishna consciousness and making it more accessible to westerners is not as crazy as I originally thought. Especially after reading the Foreword to Volume 8 by Patrick Garrison.

Clearly Keith’s ideas were endearing to many, and for good reason. One of your greatest contributions to this monumental biography/history is that you present multiple perspectives. Hats off to you. The result is that you’ve opened my (sometimes) closed mind. It’s been too easy to discard Keith as a “crazy man.” But you’ve mentioned over and over in your works that humans are way more complex than a simple label.

I reflect on the fact that the more evil any one person is perceived to be, the easier it is to lazily discard and label said person as evil or crazy and be done, instead of developing a curiosity and asking why, or looking into the complexity of a person’s character. It took eight volumes, but you finally did it!

During the first seven volumes of Gold, Guns and God, I refrained from writing much about me. My books are, of course, not about me. They are about Swami Bhaktipada and New Vrindaban. However, how could I not write about myself in this particular volume? Some readers might notice that I appear in 25 photos in the Photo Gallery. And for good reason. This book is, to a great extent, about the music at New Vrindaban, and I served in the capacity of New Vrindaban’s Minister of Music for nearly six years.

Music was a very important part of Bhaktipada’s vision for preaching Krishna consciousness and I became an important part of his mission. Bhaktipada even wrote in one of his books, “Krishna clearly says in the Gita that one with a vision for preaching is most dear to him, and I think that the vision he has given me in regard to preaching with music is best understood by Hrishikesh. So please, just follow his direction and be united in love for one another, because that is what pleases Krishna and Guru.” (How to Love God: 1992)

For those who may be curious to hear what our music sounded like at New Vrindaban, you will find—at the end of Chapter 85—hyperlinks to online recordings of the music I helped create during Bhaktipada’s Great Experiment. Perhaps some readers (and listeners) may also come to appreciate our heartfelt musical endeavors at the City of God.

The author

October 31, 2022

Temecula, California

| Back to: Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 8 |